PrivacyX newsletter #1 A global view of AI Regulation

A look at the different forms of regulation for AI globally, how the different forms need to work together as a overall system and likely direction

Welcome to issue #1

Thanks for reading the first ever newsletter from PrivacyX Consulting. I founded the company in 2022 to provide strategic advice and support for organisations related to digital policy challenges - spanning data protection, international data flows, AI, online safety, child privacy, freedom of information and open data. I’ve worked with governments, international organisations, regulators and multi-national companies on these challenges. I’m also a Visiting Policy Fellow at the Oxford Internet Institute, working on research about the impact of social media recommender systems on children. I also work as a special advisor for the law firm Allen and Overy. This newsletter represents my own personal views and does not represent any of the organisations I work with.

Before founding PrivacyX I worked for the UK data protection and freedom of Information regulator, the ICO, for 15 years. For six years I was Deputy Information Commissioner, responsible for policy and regulatory strategy. During this time I represented the ICO on the European Data Protection Board (until Brexit) and also oversaw the ICO’s guidance programme in the runup to GDPR implementation. From 2019 to 2022 I was also Chair of the OECD Working Party on Data Governance and Privacy. My policy work also involved the development and implementation of the ICO’s Age Appropriate Design Code (or children’s code).

Thank you for taking the time to subscribe to the newsletter. There are so many newsletters, blogs and social media posts out there, I really appreciate you adding my content to your ever-busy inbox! I plan to produce the newsletter on a monthly basis, covering a different digital policy theme each month, bringing together a strategic policy perspective and pointing to further reading and resources I’ve found useful. I will also use it to highlight the research I’ve produced, including my work at Oxford.

In future newsletters I plan to cover: the debate about contextual v behavioral advertising, use of personal data in elections, the UK Data Protection and Digital Information Bill and the Indian Digital Personal Data Protection Act.

If you’ve found it useful please pass it on!

Regards, Steve (contact me via LinkedIn)

For the first newsletter I’ve sought to focus on AI regulation at global level.

AI: existential risks and unlocking transformational benefits

The Economist sums up the challenge of understanding existential AI risk scenarios well in their recent article: “How to worry wisely about artificial intelligence”.

The degree of existential risk posed by ai has been hotly debated. Experts are divided. In a survey of ai researchers carried out in 2022, 48% thought there was at least a 10% chance that ai’s impact would be “extremely bad (eg, human extinction)”. But 25% said the risk was 0%; the median researcher put the risk at 5%. The nightmare is that an advanced ai causes harm on a massive scale, by making poisons or viruses, or persuading humans to commit terrorist acts. It need not have evil intent: researchers worry that future ais may have goals that do not align with those of their human creators.

The spectrum of evidence and expert views are significant. National and global policy makers are stepping into make judgments about how to address risks in the short, medium and long term. The widespread potential benefits from AI, in fields such as healthcare, are very well set out in the recent interim report of the Science and Technology Select Committee of the UK House of Commons. Future regulatory systems for AI have an essential function in enabling these transformational benefits in a fair and equitable way.

AI regulation at a global level: a big jigsaw puzzle

Whilst we’ve had AI principles and frameworks available at a global level for many years, governments are only now fully grasping the question of regulation. For example, the OECD’s foundational AI principles were agreed in 2019.

Generative AI’s rapid proliferation has catapulted the issue into a policy priority in countries large and small, across the world, in various stages of economic development. There has been a fairly chaotic debate about the need to address the short, medium and long term risks and which we should be worried about. I my view we can’t lose focus of any of these aspects - concerns are real right now e.g AI in recruitment and have to project forward to future risks in elections, and AI as a potential cyber or biotech weapon. I’m also starting to see references to the risks of ‘advanced AI’ and ‘frontier AI’ as terms to describe the future evolution.

It’s a momentous challenge of regulation - there needs to be space for AI to evolve, innovate, develop and allow benefits to emerge. Balanced against the need to ensure approaches to responsible safe AI development are baked in now, by design. Leaving it too late means designing and implementing regulation against a backdrop of fully realised harms and major societal concern, which heightens the challenge. We’re not there yet, but the clock is ticking.

Some resources I’ve found helpful

This blog by Arcangelo Leone de Castris at the Alan Turing Institute’s AI Standards Hub usefully sets out the approaches to ‘hard regulation’ - Canada, the EU and Brazil are all moving towards hard regulation. The blog also recognises the reality that most countries will have elements of both hard and soft regulation.

This academic article by Michael Veale, Kira Matus and Robert Gorwa is a great guide to help understand AI and global governance, the different modes of governance, the tensions between them.

Raymund Sun has developed this excellent AI regulation tracker, that follows AI laws and regulations as they are proposed around the globe.

Breaking down the issues

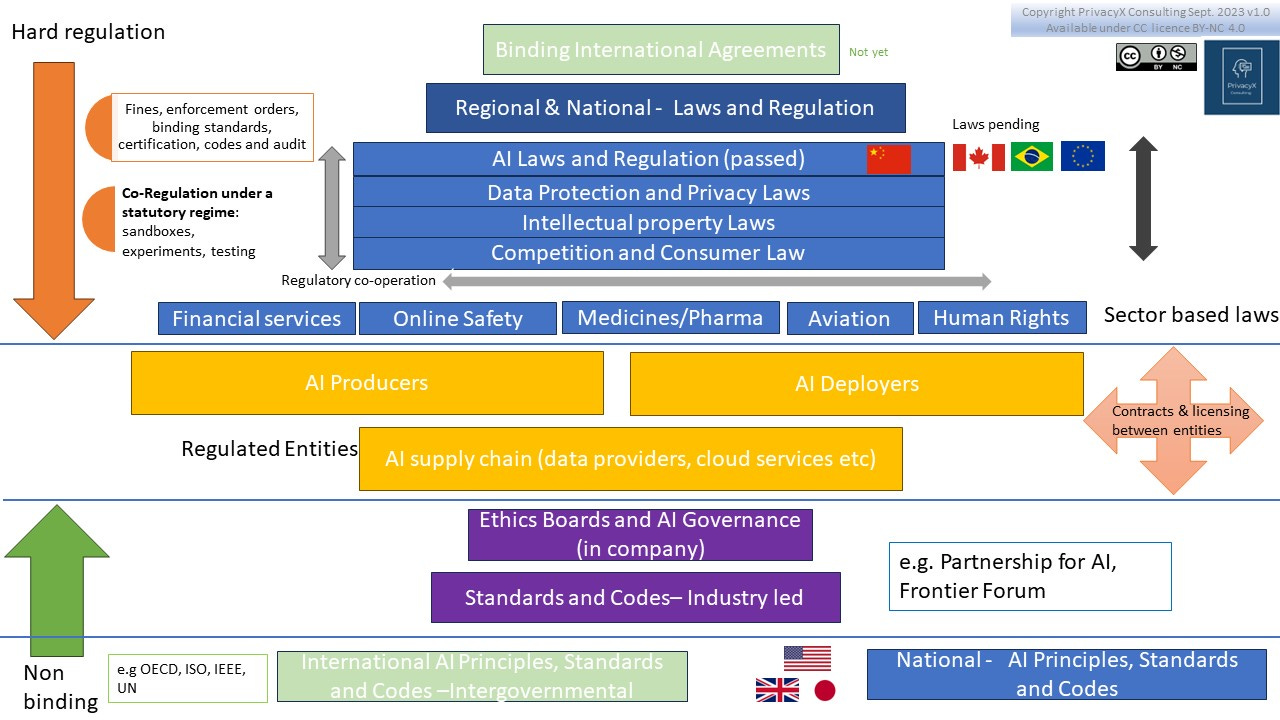

I’ve sought to visualise the key components, and the hard/soft dimension in my diagram below. It’s clear that there is no silver bullet or single solution for AI regulation. The challenges are too complex:

AI will permeate all sectors of the economy and public service delivery.

Applications of AI and their impacts and harms will vary considerably - from chatbots on e-commerce websites - to generating summaries of legal judgments - to the risks of manipulation and misinformation in elections.

AI products and services will span global borders.

There will be many different types of regulated entities involved in the AI ecosystem: providers, end users/deployers, data providers, cloud services and other intermediaries.

There is a lot convergence and agreement around the principles. Most frameworks contain well recognised principles focused on transparency, bias, fairness, risk/harm mitigation, safety, cyber security, accountability. Many of the major technology companies in this space e.g Google, Microsoft , have set out their principles and standards for responsible AI. There is therefore welcome convergence and a proactive approach from industry to implement standards. There is a also recognition that independent audit, conformance and certification may also need to play role at the higher end of risk spectrum.

There is tension about how a risk based system of regulation should be defined in a hard system of regulation. Industry is concerned that top-down regulation, such as the EU AI Act, will maintain a rigidity that could struggle to adapt to new AI products and services, and their application. This could unfairly impede innovation as the risk profile change and be slow to adapt to newer risks. Against this is the concern that a principles based system will leave too much space and discretion for industry to push boundaries and risks, without clear guardrails about what constitutes risk.

Independent regulation is also vital - to balance the evidence and make the objective judgment calls on whether risks have been mitigated and when further measures are needed. This regulation could be provided by existing regulators or by new regulators where there gaps or the risks are a high enough to justify dedicated AI oversight.

A visualisation of global AI regulation

What the diagram below seeks to illustrate:

Hard regulation/statutory/binding

International binding agreements - the ultimate global mechanism via a binding treaty. This is not on the cards yet and seems a long way off. Such an approach is likely to be developed for highest levels of risk to humanity and could ultimately involve “bans” of certain technologies and/or certain uses. The starting point is more likely to be focused on common standards, research collaboration and information sharing/alerts. International agreements could also consider fair distribution of AI benefits across the globe, recognising the different risks that could emerge as AI technologies are tested or exploited in the Global South, where different social and economic conditions could produce different results. Should this be an agreement between democratic nations under the rule law or be more inclusive and bring in countries such as China and Saudi Arabia? Who is involved will also influence where certain bars can be set. There is also a risk of creating a haven for ‘bad actors’ if it isn’t inclusive. Climate change is deemed important enough for humanity to bring everyone inside the tent, but AI is a different issue, with greater risks to human rights at its core.

Regional/national laws and regulations on AI. Currently, laws are pending in Canada, Brazil and the EU. China already has laws in place. The extent to which these mechanisms will apply will be based on risk. In Canada a new regulator will be established by the law, in the EU, member states have the choice to create a new body or add to existing bodies, such as data protection regulators. These systems of regulations allocate regulatory requirements based on risk and rely on a mix of fines, enforcement orders, binding standards, codes, certifications, approvals and audits.

AI regulators should also seek to establish an international network for co-operation swiftly, in the absence of a binding treaty. There should be a clear legal basis in national laws to enable global information sharing and joint investigations, where safeguards can be guaranteed for confidentiality and interoperability between the regimes.

Alongside these new AI laws and regulations we have long established regimes for DP, IP, competition and consumer law. These regimes are relatively well resourced in certain jurisdictions and regulators are already engaged with AI. Ensuring that these regimes are an effective layer of regulation is also essential to global AI regulation. These regulators are also starting to co-operate and work together more closely. For example, in the UK, Australia, Canada and Norway. These established regulators will also need to establish ways of working with AI regulators.

Alongside this, sector based regulators will play a key role and will also need engage in regulatory co-operation.

Across this entire regulatory system a consistent set of AI principles will be needed. The UK has focused more of its policy efforts on making these existing systems work effectively and its recent white paper indicated it that would only seek to place AI principles on a statutory footing, to guide existing regulators. In a mature regulatory system, with world leading regulators, this approach may be effective in the short and medium term, but the biggest concern will be around whether such a system leaves gaps that are not addressed, as wider cross-cutting risks and harms emerge.

I also advocate that the design and implementation of AI regulation must be informed by the emerging body of academic evidence about what makes regulation effective. The balance of ex-ante and ex-post regulation is critical. The work of Professor Christopher Hodges on Outcome-Based Cooperative Regulation should be an important input when considering how AI regulation globally can be designed to prevent the greatest risks and harms. Effective enforcement tools will of course be needed - the benefits to be gained from the mis-use of AI will be considerable and real sanctions must disrupt and shutdown those who seek to deliberately abuse or ignore the law. The key players must also be subject to regular and ongoing supervision.

The regulated entities. In the middle of the diagram sits a complex ecosystem of organisations. They will bind each other through contracts and licencing, which will play an important role in how risks and liabilities are distributed through the AI ecosystem.

Soft/non binding/voluntary systems

At the lower half of the diagram we have systems that industry are devising themselves, to enable trust and accountability in their products and services, with individual and corporate customers. Companies are developing their own standards and risk management programmes, sometimes guided by ethics boards. These standards are also developed by stakeholder groups such as the Partnership for AI and the Frontier Forum.

Alongside this longstanding international organisations such as OECD, ISO and IEEE are producing standards and principles that organisations can implement and adapt to implement their AI governance. They can also use their conformance to demonstrate the safety and risk level of their AI.

National governments are also issuing non-binding codes and principles. In some cases as an interim measure before binding regulation. The EU intends to do this ahead of the AI Act and Canada has just issued a consultation on a voluntary code for generative AI.

Do we need an international an International Atomic Energy Authority equivalent for AI?

As the 2023 AI debate raged, this question has repeatedly emerged, alongside questions about whether we need a system of testing and certification that works across borders, as for drugs and medicine regulation.

The answer on whether we need an IAEA for AI is likely to be “not yet” but we will probably need some form of international AI safety body at some point of AI’s evolution and development, and we have to ensure it is effective before we are hit by deep impacts from advanced AI that cause direct and widespread harm.

A July 2023 paper published by staff at Google Deepmind explored models and functions of international institutions that could help manage opportunities and mitigate risks of advanced AI. They explore four complementary institutional models to support global coordination and governance functions:

An intergovernmental Commission on Frontier AI could build international consensus on opportunities and risks from advanced AI and how they may be managed. This would increase public awareness and understanding of AI prospects and issues, contribute to a scientifically informed account of AI use and risk mitigation, and be a source of expertise for policymakers.

An intergovernmental or multi-stakeholder Advanced AI Governance Organisation could help internationalise and align efforts to address global risks from advanced AI systems by setting governance norms and standards and assisting in their implementation. It may also perform compliance monitoring functions for any international governance regime.

A Frontier AI Collaborative could promote access to advanced AI as an international public-private partnership. In doing so, it would help underserved societies benefit from cutting-edge AI technology and promote international access to AI technology for safety and governance objectives.

An AI Safety Project could bring together leading researchers and engineers, and provide them with access to computation resources and advanced AI models for research into technical mitigations of AI risks. This would promote AI safety research and development by increasing its scale, resourcing, and coordination.

How much are governments willing to pool globally? This is an interesting question in a time of such global tension and retrenchment. Though current EU-US engagement on digital policy and data flows, and the rise in prominence of the OECD’s digital policy instruments and outputs also provides some optimism.

Spotlight on the UK as they host the AI Safety Summit this autumn

The UK’s ambitions for the Summit were published on 4 September, part of ongoing and extensive stakeholder consultation on what the key issues are for the agenda. A feature of the ambitions seems to be a focus on ‘frontier AI’ and presumably where stakeholders see the risks in the long term.

The five objectives for the summit are currently:

a shared understanding of the risks posed by frontier AI and the need for action

a forward process for international collaboration on frontier AI safety, including how best to support national and international frameworks

appropriate measures which individual organisations should take to increase frontier AI safety

areas for potential collaboration on AI safety research, including evaluating model capabilities and the development of new standards to support governance

showcase how ensuring the safe development of AI will enable AI to be used for good globally

This article provides relevant analysis of the UK approach to AI regulation:

Roberts, Huw et al. Artificial Intelligence Regulation in the United Kingdom: A Path to Good Governance and Global Leadership? (May 1, 2023). Internet Policy Review, Available at SSRN

Closing

There are so many different policy questions and interlocking components to consider in global AI regulation. Charting a path through this will require extensive international collaboration and a will ensure that global consistency will not be sacrificed too often for national agendas, and that a diverse range of countries have an opportunity to shape the policy agenda.

As noted above, there is not a silver bullet solution and effective regulation will require effective coordination between existing and newly devised laws systems of regulation. Regulation must ensure that safety and protections are designed in - scaling with risk and proportionate to benefits.

Coming soon

If you have suggestions for future newsletters or would like to add any comments or suggestions, or learn more about PrivacyX, please contact me via LinkedIn.

Other publications

You can also find more information about other articles and publications I’ve written.

Re-use and copyright

If you would like to re-use the article content and/or the infographic they are available under a Creative Commons BY-NC license. This allows re-users to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format for noncommercial purposes only, and only so long as attribution is given to the creator.